Corruption should be the “catch word” for the next president of Uganda

By Drone Writer

You and I will agree that corruption should be the catch word for the next president of Uganda. Ugandans are tired of “untouchables.

Media attention of Uganda’s corruption often focuses on the “big fish who got away” and who were allegedly protected from prosecution by other elites. Solutions—often proposed and supported by international donors—usually rely on technical responses. Those responses overlook what, based on past actions, can be described as the government’s deep-rooted lack of political will to address corruption at the highest levels and importantly, to set an example—starting from the top—that graft will not be tolerated.

Yet, “Untouchables. Come rain, come shine, they’re never going to court, not while there’s somebody close to them in power. That’s because of the politics involved.”

—Prosecutor in the Anti-Corruption Court, May 21, 2013, “This court is tired of trying tilapias when crocodiles are left swimming.”

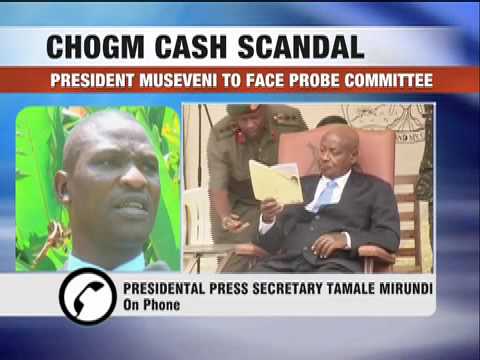

—Justice John Bosco Katutsi, former head of the Anti-Corruption Court, during a ruling convicting an engineer during the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting scandal, June 29, 2010.

“Someone will ask, ‘Will it pay?’ If it will, one will steal. If it won’t pay, one won’t steal. It should be too expensive to steal. This is why corruption is happening on a grand scale. They must steal enough to stay out of jail.”

The news that US$12.7 million in donor funds had been embezzled from Uganda’s Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) hit the headlines in many donor capitals in late 2012, prompting serious questions about Uganda’s commitment to fight corruption.

The stolen donor funds were earmarked as crucial support for rebuilding northern Uganda, ravaged by a 20-year war, and Karamoja, Uganda’s poorest region. Approximately 30 percent of the national budget came from foreign aid in 2012. As a result of the OPM scandal and claims that the money was funneled into private accounts, the European Union, United Kingdom, Germany, Denmark, Ireland, and Norway suspended aid.

The OPM scandal was not the first time that grand scale theft of public money deprived some of Uganda’s poorest citizens of better access to fundamental services such as health and education. Past corruption scandals have had a direct impact on human rights.

For example, millions of dollars’ worth of funds were diverted from the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation in 2006 and from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria in 2005. Despite investigations, none of the high-ranking government officials who managed the implicated offices have faced criminal sanction.

Most often they have remained in office, untouched, while individuals working at the technical level have faced prosecution and, in some cases, jail time. Even when ministers have been forced to resign from office, such resignations have been temporary; they were eventually reappointed to key positions in government, in what one diplomatic representative calls a “game of musical chairs.” Years of evidence indicate that Uganda’s current political system is built on patronage and that ultimately high-level corruption is rewarded rather than punished.